i want to earn back my body’s trust

holding the grief of cognitive decline and navigating chronic illness induced brain fog. healing from self-neglect, no longer pushing through pain, and what it means to earn back my body’s trust

(cw: nondescript mentions of abuse. descriptions of chronic pain and emotional self-neglect as a trauma response. i share this as an invitation to hold yourself and any emotions that come up, whether that be with a deep breath, a pause, some company, or any other accessible care your mindbodyheart may call for. your wellbeing means a great deal to me. you deserve tenderness and grace)

Since becoming chronically ill, my capacity to speak, read, write, and think has been irreparably changed by unending brain fog. I ache for language, for writing — a prayer, that I hope can reach someone who will care enough to understand what it means to suffer from this illness.1 But all I find is my tongue, which never unties and my hands, searching desperately for words on an unlit ground, holding them in palm, feeling their weight, only for my fingers to be too weakened to bring them to the light. There are many days my cognitive decline is more painful to cope with than my throbbing bones.

Bedbound by unending symptoms and debilitating chronic pain, to manage my severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Fibromyalgia, I am confined to a darkened room with minimal stimuli. All mental, emotional, and physical exertion is enough to trigger a crash,2 or worsen my baseline; even crying to process my loss of capacity or daydreaming to cope could be enough to set me back for days, weeks, months.

My body exists in a sunless space, where not even a shadow of my former self remains — only fog. In this fog, I am suffocating.

Losing more of my ability to speak (let alone think) due to the intensity of my cognitive decline, I am confronted with what it means to be in community when I am unable to show up in all the ways I’ve previously known.

For as long as I can remember, I always had more curiosity than my body could hold: it would come out in my endless questions to friends, intuitions that pulled me towards strangers, and an unwavering will to learn and care deeply for all things. This is one of the ways my AuDHD manifests.

Before becoming chronically ill, during my undergraduate studies, I had the privilege of building relationships with professors I adored who became beloved mentors. Since childhood, writing and reading were two of my dearest companions. The “classroom,” which I found mostly in community beyond school, was a site of sacred dialogue and joy, where my curiosity could exist unbound. Learning from Black feminist theory, and queer postcolonial feminist literature by femmes of the global majority — Audre Lorde, Sherronda J. Brown, Brinda Mehta, and Jean-Charles Régine are just a few of the people whose experiences, analysis, and work continue to inform my politics to this day. I was guided, first and foremost, towards finding wisdom from eroticism, embodiment, my loved ones, and the land. Joy was spending the evening texts by these writers and the light of the setting sun, annotating hundreds of pages, often daily. I felt connected to the world in a way I’d longed for my whole life: challenged, held, and nurtured as I had never been.

Since my first semester of college, I knew I wanted my thesis to be on asexuality and its intersection with race. While this one of my oldest special interests, I was also acutely aware of the fact that, too often, our existence is constrained by violence, mystified, and “erased.” Creating spaces where other asexual people of color could be seen and heard in their asexuality (often for the first time) was to know, with clarity, of all the timelines in existence, this (this!) is the one I’d choose. When I was invited to develop policies to support asexual people and present our research on a national scale, I was over the moon. My asexual kin deserve this visibility! Alongside organizing, the community I’d built beyond school, and the fact I was finally writing again, I felt that I was walking towards my purpose.

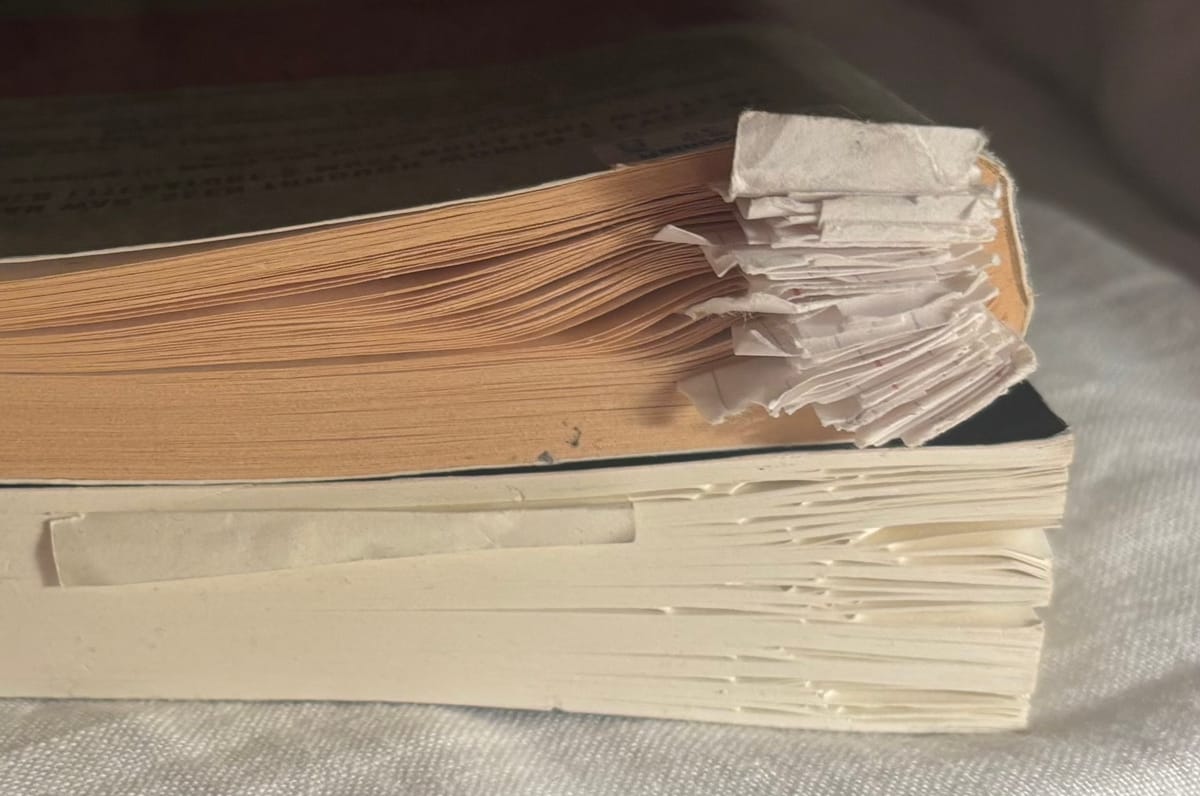

image of two of my books, heavily annotated (“children of the new world” by assia djebar and “in the dream house” by carmen maria machado) stacked on top of each other. all the texts i’ve studied and loved are like this 。⋆₊⊹

What I was entirely unprepared for was the sheer social exposure college provided. The deep curiosity I felt for other people, when combined with my unhealed trauma, had consequences I am left to bear the weight of today.

The abuse I experienced growing up left me with a nervous system that believed I was responsible for everyone’s mood, and existed solely to give care and withstand pain. This translated from my family life into my interpersonal relations. I unconsciously chose friends who could not or did not reciprocate an interest in my needs or inner world because these dynamics were familiar. I was constantly taking on the feelings of those around me with no boundaries of my own. I only knew how to give myself away. I learned to weather the worst and called it devotion.

As a result of my history, compounded by the gendered racial violence I later experienced in college that led to my PTSD, my health began to noticeably decline. The persistent pain in my neck felt as though I was constantly being choked by someone standing behind me. I was plagued by nightmares that made me fearful of sleep, but still awoke to a reality that was no better. The nightsweats I had developed would wet my bed in their entirety. I started sleeping on the cold marble floor of my dorm room to try to regulate my body heat, but this helped barely. Even wearing clothes felt like being bound by barbed wire. Despite my weakness and fatigue and the brain fog that was making it impossible to read and write (which meant loosing two of my favorite practices), instead of slowing down, I worked twice as hard. For every pain I felt, I demanded more from body.

My relationship with school was becoming increasingly rigid — what used to be motivated by excitement and curiosity became the only aspect of my life I felt I had any control over, so I instead forced myself to show up, without rest, without care. Every project, every assignment got more effort and attention than I ever gave myself. By this point, I was self-isolating to cope with my PTSD. My flashbacks and nightmares were relentless, and my physical symptoms had become too severe to hide. I believed my pain made be burdensome, so I kept myself at a far enough distance from friends that I couldn’t be seen at all. In doing so, I abandoned my body. I abandoned myself.

Following months of grueling blood tests and x-rays, I was called by a number I didn’t recognize. In a low voice, the person on the other end of the line introduced themselves as an oncologist, the head of his department. Devastation shot through me like a cold bullet. I couldn’t say a word in return.

“Things look really serious. Which state do you want to do chemo in? You should come home to be with your family.”

It was only then, as he spoke to me, that the weight of my entire year came crashing down on my chest. In the emptiness of my dorm room, I wept for perhaps the first time in months.

While on medical leave we would learn I do not seem to have cancer, I received countless other diagnoses instead. After a lifetime of chronic pain that begged me to attune to my unmet needs, my body finally gave way to chronic illness: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Fibromyaglia so severe, I had to rely on care of others if I wished to survive.

My body needed me to slow down whether I was ready to or not.

Although my curiosity remains as big as it’s ever been, most days, I am devastated by the severity of my brain fog. All my desires are now too far out of reach. I am unable to read or comprehend the books I adore. I am unable to continue the projects I worked years to develop. I am unable to access school. I am unable to form the questions and analysis my body still begs for. Conversation is impossible more often than it’s not, and even minimal talking has an impact on my baseline. I struggle to experience most media, and if I’m able to listen to an audio or watch a video, chances are, I will barely understand it. I go months at a time unable to see anyone but my caregivers. I tend to forget things soon after I hear them. I can rarely write (usually one essay a month if I’m lucky). My body no longer allows me to overexert myself in the name of support in all the ways I (unsustainably) used to. Even these examples do not include what I physically cannot manage (which is a far more extensive list).

I lost everything I knew about myself to chronic illness. But in this, I gained a new life too, one that sees my full humanity.

Becoming disabled was a rebirth, it was an invitation for me to embody my own politics of care, ask for help, and believe that I deserve tending to. Managing my M.E. and Fibro requires me to attune to my needs and feelings in ways I went most of life without. How I navigated my relationships and commitments before disablement were always unsustainable and at my expense. To survive severe M.E., I must allow myself to be held and witnessed, even when I cannot be in service others, despite the trauma that taught me this was all I was good for. I now carefully pick and choose what gets my limited energy, and in doing so, I learn to treat myself as something precious. My disablement reminds me that we are meant to be supported by the collective, and that each of us is a universe, sacred simply because we exist.

Chronic illness has taught me to slow down. I am more present with myself than I ever was. I am finding news ways to live beyond the violent constraints of capitalism, which demands production above all else. While this has changed me, I revolt against the idea that pain always has to have a lesson. How do I deny myself the right to feel (deeply, completely, messily) in my effort to learn?

Allowing myself to be held by community has helped me to heal in ways we otherwise cannot access alone. This is an imperfect process. Being seen in my grief continues to terrify me. I feel this as a red hot panic through my body. I am always looking for an exit, as if I am actively being hunted, even if it is just me and a dear friend in a room.

I remind myself healing is nonlinear: it cannot be measured in steps forward or backward. Perhaps it is just about staying in movement — all the big and small ways we affirm to ourselves, I will not abandon you. As in, maybe I can’t can’t help but learn as long as I love, and I can’t help but love as long as I’m here. As in, there will be moments when it is enough for me to feel without thinking. I do not need to understand my grief to notice it — to invite it from the rain torn porch to the dinner table. To look it in the eyes as we share a meal and thaw by the fire. How alive I am to feel all this!

Today, I forgive myself for my self-neglect. Our bodies know we deserve protection. Dissociation was the only tool I had at the time to survive the harm we were actively enduring. Now that I am safe enough to tend to my grief, it breaks me into pieces, but in doing so, it has also opened my heart to the world. The love this has welcomed into my life has changed me entirely. I feel everything more deeply, including my joy and need for care.

I am finally learning what it means to accommodate myself and be accommodated. On higher capacity days, I love to be read to. Rewatching media I’ve already seen is a meaningful way to limit my cognitive exertion. I ask for summaries and clarification often. I use text to speech transcriptions. If I can’t make sense of an video, I focus on its sound, if I can’t make sense of its sound, I focus on its colors, if I can’t focus on its colors, I practice holding myself gently. I set boundaries with my friends. I teach people what it means to love me well. I learn imperfectly and forget things without shame.3 I bring my grief to the light. I feel it in all the ways I can.

I want to spend the rest of my life trying to earn back my body’s trust.

I want her to know she’s safe with me.

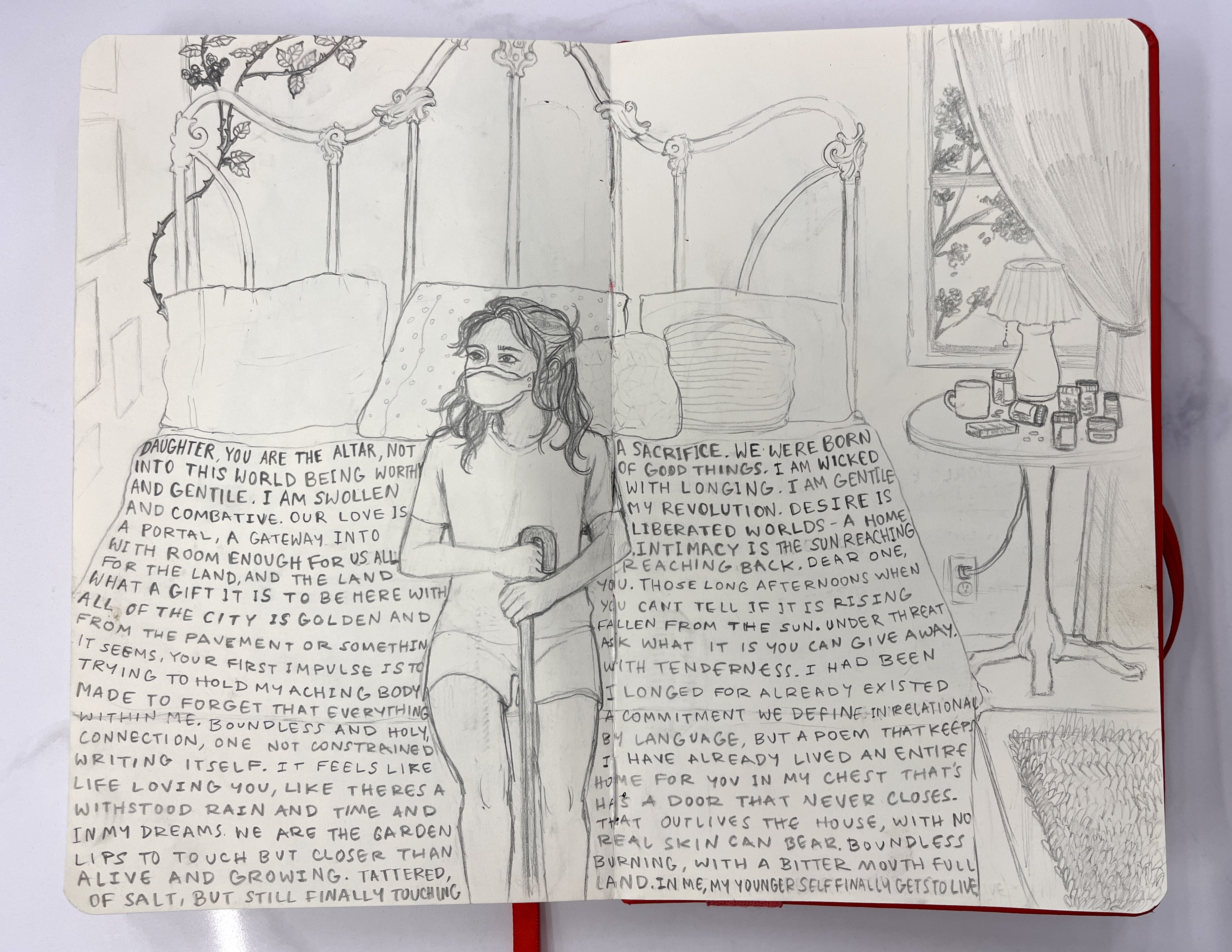

art made by my dear friend ada.rsd on instagram. a drawing of me (a masked chinesewhite femme with hair below my shoulders) holding my cane in my sickbed. the sheets on the bed are filled with excerpts of my writing which reads “daughter you are the altar, not a sacrifice. we were born into this world being worthy of good things. i am wicked and gentle. i am swollen with longing. i am gentle and combative. our love is my revolution. desire is a portal, a gateway into liberated worlds - a home with enough room for all of us. intimacy is the sun reaching for the land and the land reaching back. dear one, what a gift it is to be here with you. those long afternoons, when all of the city is golden and you can’t tell if it is rising from the pavement or fallen from the sun. under threat, it seems your first impulse is to ask what it is you can give away. trying to hold my aching body with tenderness. i had been made to forget that everything i longed for already existed within me. boundless and holy, a commitment we define in relational connection, one not constrained by language, but a poem that keeps writing itself. it feels like i have already lived an entire life loving you, like there’s a home for you in my chest that’s withstood rain and time as has a door that never closes. in my dreams we are the garden that outlives the house, with no lips to touch but closer than real skin can bear. boundless, alive and growing. tattered, burning, with a bitter mouth full of salt, but still finally touching land. in me, my younger self finally gets to live.” on the right of the drawing is a bedside table with a weekly pill organizer, numerous medicine bottles, and a mug

💌🌱🌱 for those who would like to support me monetarily, my v 3 n m 0 & c a s h a p p are solenneh. as a severely disabled femme who is otherwise unable to work, all fun/dz will go towards compensating my caregivers. thank you dearly

I am beyond grateful to be in community with other people who grasp the severity of M.E. — however, this often comes from personal experience with this devastating disease. Many of us are forced to use the little capacity we have left to spread awareness about this chronic illness in order to access the support we need to survive, and often, these efforts only worsen our baseline. We deserve better. For pre-disabled folks who have the means or capacity to uplift this advocacy, contribute funding directly to people’s m00tual a!d campaigns, and/or M.E. research, please show up however you’re able! We need you. We need each other <3 ↩

An M.E. crash is defined as “‘temporary period of immobilizing physical and/or cognitive exhaustion’ resulting from post-exertional malaise. A crash may also be referred to as a symptoms flare-up, flare or even “collapse”.” ↩

This is an intention and an ongoing process. I still struggle to cope with how much I forget since becoming chronically ill, but I want to learn what it means to grieve and forgive myself for what is out of my control ↩